We would like to tell you about the pharmacy premises, the daily work of pharmacists, and the many processes that remained hidden from the everyday visitor, as well as how pharmacies operated in the city of Ogre.

For those of us accustomed to buying ready-made packages, this story reveals a completely different world.

Since ancient times, pharmacy visitors have relied on the pharmacist’s knowledge. Pharmacists were sometimes even called ‘doctor’, a title that reflected the high level of trust placed in them. At the Ogre pharmacy, staff occasionally had to listen to a patient’s entire medical history in order to decide what medicine to dispense when there was no prescription.

‘Not everyone can work as a doctor, a nurse, or a pharmacist. A pharmacist’s work requires precision down to the milligram, the ability to concentrate, to be perceptive and attentive – even meticulous. One must be able to read all kinds of handwriting; cleanliness and order must be second nature,’ said Rasma Hartmane, former head of the Ogre pharmacy.

If a prescription was difficult to decipher, people would joke – as they still do today – that it was simply a doctor’s handwriting, something only the pharmacy could interpret, no matter how mysterious the hieroglyphs.

To avoid misunderstandings, each doctor had their own stamp. On the rare occasions when even a pharmacy employee could not read a prescription, the doctor would be contacted directly. However, this seldom happened, as pharmacists were truly skilled readers of handwriting.

In the 1950s, the Ogre pharmacy used the so-called burette system, or ‘pharmacy organ’, for preparing medicines. At the time, it was considered modern equipment and was rarely found in provincial pharmacies. Ready-made medicinal solutions of specific concentrations were stored in glass containers and flowed through glass tubes resembling organ pipes into bottles, allowing even complex medicines to be prepared within minutes.

Many people have heard the saying ‘weighed like in a pharmacy’. This refers to the precise hand scales used to prepare powders, ointments, and medicines. With them, even the smallest quantities could be measured. The greatest care was required when working with poisons; to make dosing easier, they were often mixed with sugar before weighing.

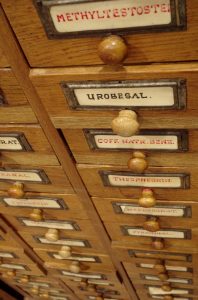

Inside the pharmacy cabinets were labelled sections with names such as ‘Heroica’ and ‘Venera’. The first contained very potent substances, the second poisons. Arsenic was stored separately in a locked compartment.

At that time, no pharmacy could function without preparing sterile solutions. In the Ogre pharmacy, a small glass cabinet was set up for this purpose, where injectable solutions were prepared. Distilled water, essential for medicine production, was obtained on site in the pharmacy kitchen, where a boiler with an automatic filling system and a cooling unit were installed. Medicine bottles were also sterilised there, and a special electric drying cabinet was used in the process.

There was a separate room for storing medicines and dressing materials. The walls were lined with cabinets fitted with revolving shelves, making it easy to store and retrieve items. More than 2,000 different medicines were kept in the pharmacy. Many had strong odours, some were flammable, so careful organisation was essential to ensure both safety and preservation.

On the third floor was a drying room where medicinal herbs were dried and raw materials stored. Herbal substances played a very important role in medicine preparation at the time; historical sources indicate that in the 1950s, nearly 40% of medicines were made from plant-based raw materials.

In the 1950s, the Ogre pharmacy also had spacious basement rooms, although groundwater sometimes flooded the floors. Antibiotics and serums, which required low temperatures, were stored there. Various ointments were kept in galvanised tin containers.

In the pharmacy’s courtyard, tons of chlorinated lime, gypsum, numerous oxygen cylinders, and packaging materials were stored in a warehouse.

Every month, three to five truckloads of medicines and pharmaceutical supplies were delivered from the warehouses of the Main Pharmacy Administration to the Ogre pharmacy. In the 1950s, the pharmacy served not only the city’s residents, the hospital, and three sanatoriums, but also pharmacy points in Ikšķile, Tīnūži, and Krape, as well as the surrounding rural population.

To reduce congestion and long queues, in the 1960s, a pharmacy point was opened at the Ogre Polyclinic. There, customers could purchase ready-made medicines or collect prescriptions that had already been prepared. Prescriptions could also be submitted at the polyclinic. If medicine was urgently needed, the polyclinic would call the pharmacy and provide the prescription details. By the time the patient arrived at the pharmacy, the medicine would already be prepared.

However, prescribing and handing over the medicine was far from simple. First, the prescription received at the pharmacy was reviewed by a pharmacist, who checked the physical, chemical, and pharmacological compatibility of the substances and verified that the dosages were within permitted limits. If anything was unclear or incorrect, the prescribing doctor was contacted immediately. Once approved, the prescription was passed to an assistant for preparation. The finished medicine was then checked again by chemist-analysts to ensure it matched the prescription exactly. Only after this careful verification did the pharmacist dispense the medicine to the customer, confirming the surname and repeating the usage instructions.

‘A pharmacist must not make mistakes,’ said pharmacy manager Valērija Jukmane, ‘because it can cost a life’ (Padomju Ceļš, October 17, 1967). Pharmacist Vilma Roga described internal practice as follows: ‘Old pharmacists once taught me: check the label on the medicine bottle three times – first when you take it from the shelf, second when you prepare the medicine, and third when you return it to its place’ (Padomju Ceļš, July 7, 1984).

The entire preparation process usually took no more than two hours. There were exceptions: if medicine was needed for a child, it was prepared within half an hour. Pharmacy staff also tried to accommodate rural residents who needed to catch public transport. The seriousness of the illness was taken into account, as was the practice at the polyclinic pharmacy, where prescriptions were sometimes dictated by telephone.

Ogre Central Pharmacy also offered home delivery of medicines upon request. Deliveries were carried out by pharmacy employees and occasionally by students who came to assist. For rural residents, medicines were often delivered by emergency medical personnel.

In the 1960s, the Ogre District Central Pharmacy was one of the largest in the Riga region and also served as a methodological centre. Immediately after the war, only three employees worked there; in the 1950s, there were ten, but by 1967 the staff had grown to 51 people, although visitors typically saw only two or three at the counter. This growth was reflected in turnover figures as well – from 2,100 roubles per year to 300,000 roubles.

From the early 1970s, when the Ogre knitwear factory began operating, the city’s population increased significantly due to the arrival of workers from other regions. At that time, the pharmacy served a hospital and sanatoriums with around 1,000 beds, as well as the polyclinic, the railway workers’ prophylactic clinic, preschool institutions, both vocational technical schools, and nearby medical points. It also operated as an on-call pharmacy, meaning essential items could be obtained at any time of day or night, including Sundays. The increase in population was clearly felt – the pharmacy processed around 500 prescriptions daily.

‘Scales in hand, and standing on your feet for all seven hours, you weigh, measure, mix, stir,’ pharmacist Vilma Roga of the polyclinic pharmacy point once told the newspaper Padomju Ceļš.

Students from Ogre Secondary School were widely involved in auxiliary tasks – packaging medicines and carrying out sanitary work. The pharmacy premises had long become cramped and uncomfortable and were in urgent need of reconstruction.

In 1978, pharmacies in the Ogre district dispensed medicines for 1,049,000 prescriptions. The turnover reached 773,000 roubles – medicines worth 13.63 roubles per district resident, including children, which was a considerable sum at the time. Almost ten years later, in 1987, district residents purchased medicines worth 819,000 roubles.

In 1979, there were ten pharmacies in the Ogre district employing 98 people: 14 provisors, 30 pharmacists, and two nurses.

From the early 1980s, pharmacy manager Rasma Hartmane and her deputy Dzidra Taranova led classes for students in the medical stream at the production training complex. They introduced students to the daily work of pharmacy staff and organised practical training at the pharmacy. Every summer, several students worked there as packagers, and some later continued their studies at the Riga Medical Institute in order to pursue careers in pharmacy.

Until 1982, Ogre Central Pharmacy was the only pharmacy in the city. When a second pharmacy opened at Padomju Prospekts 9 (now Mālkalnes Prospekts), it became possible to consider reconstructing and adapting the central pharmacy to accommodate a larger flow of customers.

By 1985, eleven pharmacies operated in the Ogre district with 103 employees. Of these, 52 were specialists with higher or secondary professional education, and almost half had more than 20 years of work experience.

During the reconstruction of Ogre Central Pharmacy in 1987, the heaviest workload fell on the pharmacy at Padomju (now Mālkalnes) Prospekts. The pharmacy point at the district polyclinic continued to operate, and in September, a pharmacy kiosk was opened at Ogre railway station so that residents from the town centre would not need to travel to Padomju Prospekts. However, only non-prescription medicines were available at the kiosk. For a fee of 1.7 roubles (or 2 roubles if ordered by phone) and upon presentation of a prescription, medicines and spectacles could be delivered to one’s home.

Although historical materials and periodicals show that during the Soviet years, the work and achievements of pharmacies – like everything else – were publicly praised for fulfilling and overfulfilling plans, the daily reality and working conditions were often harsh, even fifty years after the war. For those who did not experience the Soviet period, it is difficult to imagine that even plastic containers were scarce in an institution such as a pharmacy.

‘In the past, each pharmacy had its distinctive signatures, its own labels. You could look at a bottle and know which pharmacy it came from. Powders were wrapped in ordinary paper, parchment, or wax capsules. We only had the first, which quickly absorbs moisture. Powders should already be industrially prepared; instead, we mix and prepare thousands ourselves. Soda and boric acid arrive in 40-kilogram sacks, cotton wool in 50-kilogram bales. Try lifting them and then packaging them into 100-gram portions… There is a shortage of wrapping paper, measuring cups, and flasks of the required volume. Plastic containers – light, unbreakable – electronic scales, calculators, all seem like an unattainable dream. And the medicines… I look with sad eyes at everything that can be bought at Moscow airport kiosks. It is not right that the purchase of imported medicines is rapidly decreasing. But what can we offer in return? Besides, if a medicine sits in cupboards for a couple of years, as they say, its production must be stopped. The mandatory assortment of medicines is completely absurd, yet inspectors still run their finger along the list – and God forbid if one of the specified items is missing. Medicines age, just like everything else in this world.’

(R. Hartmane, Padomju Ceļš, August 30, 1988.)

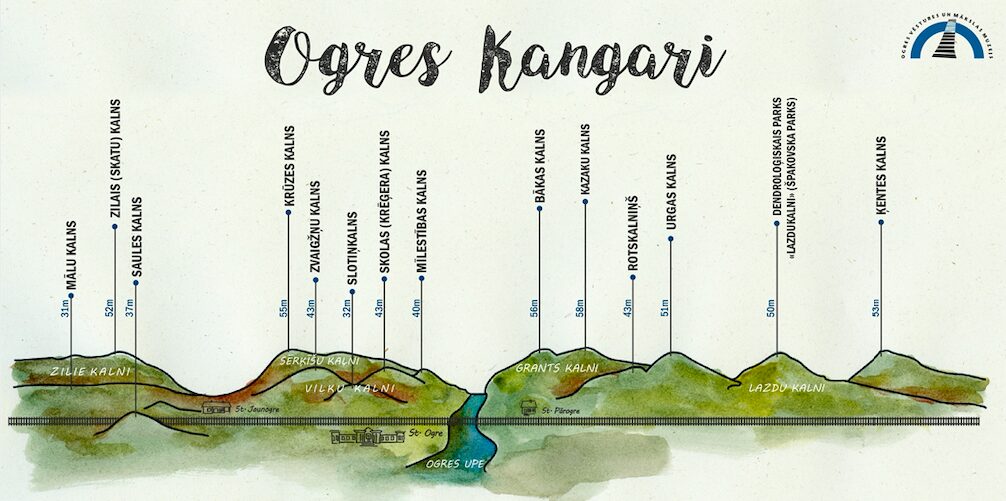

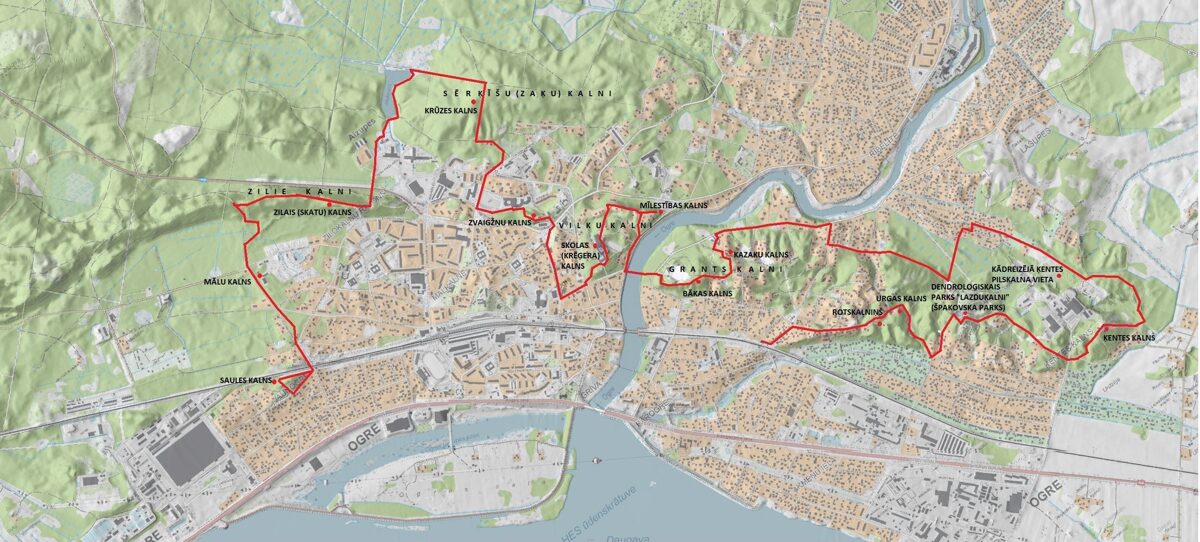

“OGRE KANGARI” HIKING TRAIL

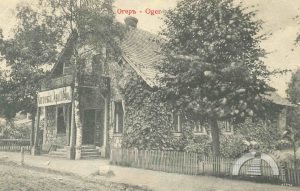

We invite you to explore the hiking trail to better discover the hills of Ogre. View the photo gallery and read the story on the museum's website or Facebook page. By looking at historical images, you can compare how the city has changed over time.

We have marked the route in the

"BalticMaps" map browser.

The “GPX” file is convenient to use with the LVM GEO mobile app.

The total length of the hiking trail marked on the map is 14 kilometers (7 kilometers in Pārogre and 7 kilometers in Ogre center and Jaunogre).

The hiking trail winds through both the urban part of the city (with asphalt, cobblestone, and gravel surfaces) and green areas (park paths and pedestrian-trodden forest trails without special amenities).

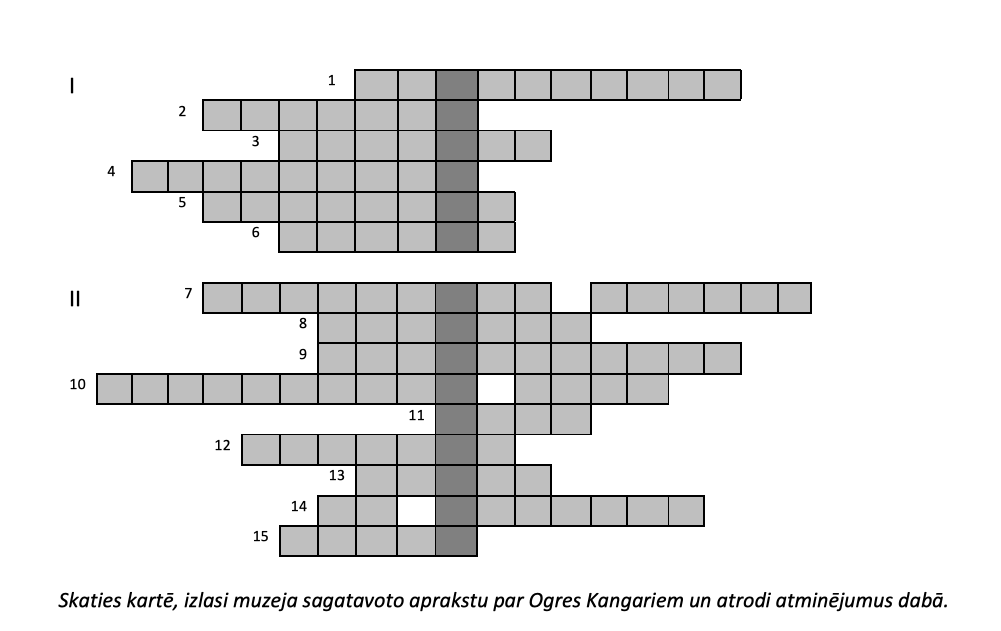

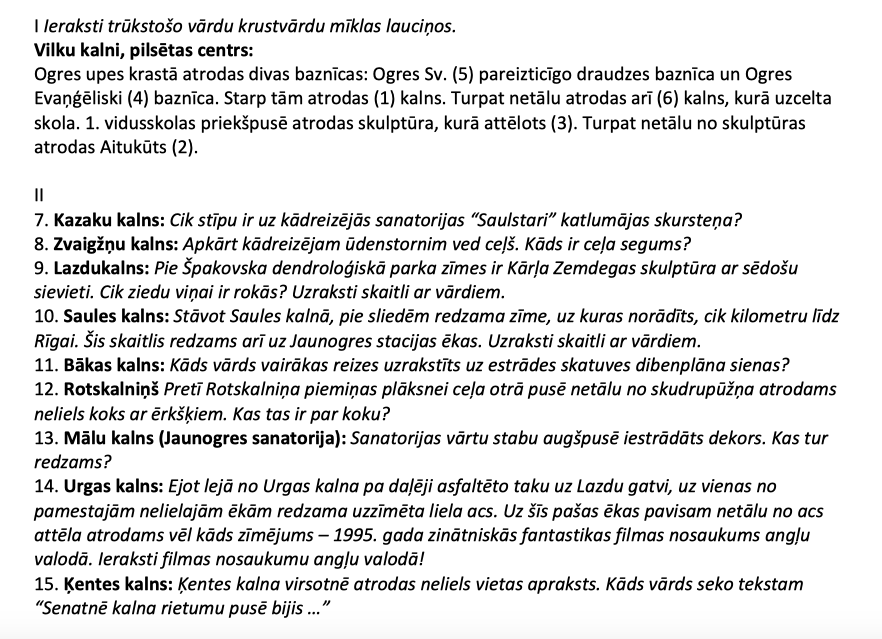

Everyone is also invited to complete a task — to solve

a crossword puzzle. Its clues can be found in places along the hiking trail. The puzzle solution can be submitted in person at the museum or sent to the email address

ogresmuzejs@ogresnovads.lv. Every solver will receive a small, museum-produced thematic souvenir — a calendar with an illustration of the Ogre Kangari hills (you will receive it upon arrival at the museum).