Siberian Notebook

The Ogre History and Art Museum is launching a new story series titled “Museum Acquisition”. The series will highlight some of the most unique items recently added to the museum’s collection. To commemorate March 25, the Day of Remembrance for the Victims of Communist Genocide, we present a story about an object used during exile […]

The Ogre History and Art Museum is launching a new story series titled “Museum Acquisition”. The series will highlight some of the most unique items recently added to the museum’s collection. To commemorate March 25, the Day of Remembrance for the Victims of Communist Genocide, we present a story about an object used during exile and preserved by its owner for decades.

March 25, 1949, remains in the memories of countless deportees as a day filled with uncertainty, fear, and grim foreboding. On that day, more than 42,000 residents of Latvia (13,504 families) were arrested and hastily deported to remote settlement areas in the USSR. Some died during the journey due to harsh living conditions – insufficient nutrition, heavy physical labour, cold, and illness. Others perished in their distant places of settlement. Many, having endured years of hardship, were able to return to Latvia in the second half of the 20th century.

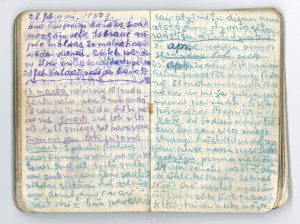

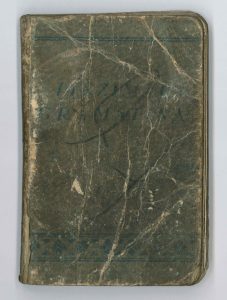

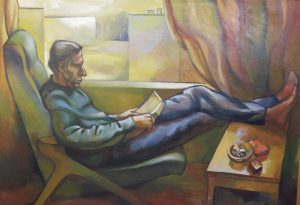

Lidija Caunīte was among the tens of thousands who managed to return. A small, yellowed notebook preserves fragments of information about her years in exile.

The pocket-sized notebook was discovered in the attic of a house on Rīgas Street in Ogre by the building’s new owner. Recognising its emotional and historical value, he brought the notebook to the museum.

In the book “The Deported: March 25, 1949”, Lidija Caunīte’s name appears among the thousands who were deported. On the morning of March 25, 1949, she, together with her daughter, brother, and father, as well as her godfather and his family, began their journey to the Teguldet District of Tomsk Oblast. In 1956, Lidija Caunīte, her brother, and her godfather’s family were released from settlement. However, the seven years spent in Siberia brought painful losses – in January 1950, Lidija’s father died at the age of 60, and in October of the same year, her four-year-old daughter Valda died of pneumonia. The brief notes in the notebook offer only glimpses into the woman’s experiences.

Notes

March 25, Friday: “Beginning of red. rev.”; “Our arrest day. We leave home at 8:30.”

March 26: “Left Ogre at 19:30”

March 27: “Crossed the Latvian border at 2:30”

The following days list the cities through which the train echelon carrying the arrested passed: “Velikiye Luki – Bolovoye – Rybinsk – Danilov – Kirov – Molotov – Sverdlovsk – Omsk – Novosibirsk – Taiga; in the evening we arrive in Tomsk…”

April 10: “Unloaded from the echelon at the refugee camp.”

April 14: “Surrendered passports”

April 16: “Beginning.”

The subsequent days in the notebook are filled in irregularly. Most entries record tasks – gathering firewood, threshing grain, mowing, milking cows, and similar work – as well as weather conditions, letters sent and received, and occasional calculations. At times, a surname appears, accompanied by notes such as “taken to the hospital; we buried [them].”

In the longer entries, sadness and nostalgia for home are evident. In December 1949, the woman writes:

“Holiday days pass in housework. In the homeland, they celebrate them differently. Last year, bright candles sparkled on our Christmas tree at home. This year there are none, and God knows what we’ll do next year.”

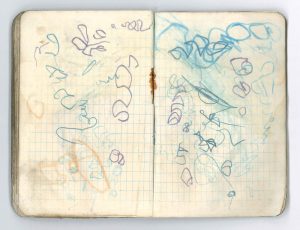

Several pages of the notebook contain scribbles, possibly drawn by the woman’s daughter Valda. On one page, amid the swirling lines, the name “Valda” is written.

More detailed descriptions of individual days appear toward the end of the notebook. For example:

“Outside, a terrible blizzard. Today I washed laundry. I also have to go for firewood, as there’s only enough for a day. On February 26, I sold father’s glasses for potatoes. On February 23 Valda was vaccinated for smallpox.”

On March 25, 1950, she writes:

“Today marks one year since we left our homeland. Outside, there’s still deep snow and a blizzard, although the sun warms more than in winter, and we think spring will be here soon too. To mark the day we left our native home, I will write a letter to my homeland.”

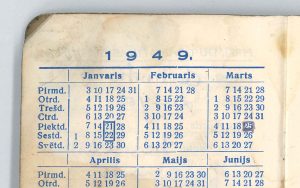

The notebook was filled over several years, and notes from 1950 sometimes appear alongside entries from 1949. It is evident that after the hardships of 1950 – especially the loss of her daughter – the woman stopped writing. The final entries, consisting of corrected day names, are dated 1957 and were most likely added so that the notebook could still be used as a calendar, even eight years after its publication.

The March 1949 deportations were primarily directed at individual peasant farms and aimed at the elimination of “kulaks as a class” (a Soviet ideological term for peasant farmers) to enable rapid, forced collectivisation. One such farm targeted for liquidation was the “Stariņi” homestead in Ikšķile parish. As a result, its residents – Lidija Caunīte’s family – were forced to leave it on the morning of March 25.

The small format of the notebook did not allow for lengthy descriptions, and most likely there was neither time nor desire for them. Nevertheless, these brief, fragmentary phrases and concise daily records form an emotionally powerful historical testimony to what March 25 truly signifies – a day on which we fly the national flag with a black mourning ribbon.

Santa Šustere,

former History Specialist at Ogre History and Art Museum